Sex Offenders Prey on Left-behind Children

A mother is overcome with emotion after her 7-year-old daughter was sexually assaulted by a middle school student in Hengyang, Hunan province, on June 27. Provided to China Daily

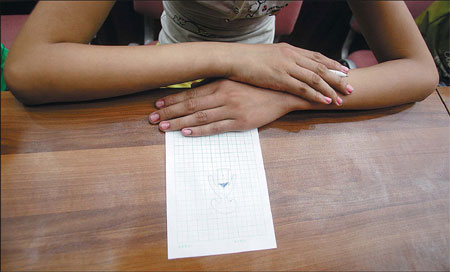

A child participates in a sex education class by drawing a picture at a primary school in Jinan, capital of Shandong province. The class is part of a course aimed at alerting children to the dangers of sexual assault. Zheng Tao / China Daily

Li Xinru (second right) with her fellow students at the primary school in Yangfan village, Shanxi province. Zhang Yuchen / China Daily

Ignorance and fear of humiliation keep many victims' families silent.

Children all over the world look forward to summer vacation. They dream of seemingly endless, lazy days with no lessons, no teachers, and nothing much to do except enjoy themselves.

But for one group of children in rural China, the two-month break is anything but a time of carefree joy. They are the 60 million "left-behind children" whose parents are migrant workers who moved to the cities in search of work. The children are usually left in the care of their grandparents, often elderly and unable to provide effective supervision.

The lack of parental protection can leave children vulnerable to all sorts of dangers, especially sexual abuse. A number of recent cases have appalled the nation and led to calls for tougher action on offenders.

Many of the attacks occur at schools. Earlier this month, a 62-year-old teacher was detained in Jiangxi province, accused of abusing seven pupils, all under the age of 9, over a six-month period.

Just a few days before that, a primary school teacher in Shanxi province was arrested on suspicion of molesting a number of pupils.

Earlier this year, a primary school principal and a government worker were detained after police claimed they had taken six young girls to hotels in Hainan province and raped them. The principal was later jailed for his part in the attacks.

In May, more than 20 cases of sexual abuse of children nationwide came to light. Many of the victims were rural left-behind children.

Going further back, of the approximately 2,600 cases involving children in Guangdong province between 2008 to June 2011, more than 75 percent concerned sexual abuse, according to a survey jointly conducted by the All-China Women's Federation and the People's Procuratorate of Guangdong province.

The survey indicated that in one village alone, 94 percent of the cases involving children were centered around sexual abuse. Approximately 67 percent of the victims were acquainted with or related to their alleged attackers.

Some observers believe that these cases, although high profile, may not reflect the true scale of the problem. "There are probably many more cases, but they just haven't been reported by the victims," said Han Jingjing, director of the Beijing Youth Legal Aid and Research Center.

Ignorance, humiliation

Some cases never come to light because the families fear the public humiliation that can accompany revelations, but other factors are also in play, including ignorance.

"The (sex) education children receive is usually inadequate. Some of the kids don't even understand what has happened to them," said Zhou Liping, director of the children's health department at Shanxi Children's and Women's Hospital.

There are no reliable statistics about the sexual abuse of children because the figures only relate to cases that are reported and go to trial. "Many children have been sexually assaulted, but we have no idea of the exact number," admitted Han.

Even the figures that are available may not tell the true story because the method of case classification makes assessment almost impossible.

"One reason is that the cases are divided into different categories, such as 'school-based sexual abuse' or 'rural sexual harassment'. The personal circumstances of the children are not stated explicitly, so it's hard to know whether they are members of the 'left-behind' group or not," said Han.

Lonely, frustrated

Of course, sexual abuse isn't the only problem facing left-behind children. Loneliness, frustration and feelings of being unwanted can also cast a shadow over these young lives.

Li Xinru stood alongside her smiling fellow students, frowning silently. The 6-year-old is one of three left-behind children who attend a village school in Linfen, Shanxi. While the other students played happily, Li rarely looked happy.

Her mother works at a printing factory in Beijing and her father is a laborer in Inner Mongolia, so the first-grade student has been left with her grandparents. Her two older brothers attend a middle school in a nearby village.

Her approach to strangers is markedly different from that of her peers. She is likely to respond to a gift, such as a snack, without a word of thanks or even the slightest change of expression.

She seldom responds to questions and is withdrawn. Her answers usually consist of just a few words: To the question "When do you call your mom?" her answer was "Dark", meaning after nightfall.

When the school held an event to mark a large donation to its building fund, the other left-behind students were surrounded by family members. Li, however, arrived alone. When asked where her grandparents were, she replied, "Watching TV at home". Her expression grew graver and sadder the more she was questioned.

Although she finds it hard to open up to strangers, she reacted quickly when asked, "Who do you prefer to be with, grandpa or your grandma?"

"I like mom most," she said. She made no mention of her brothers.

Company rules mean Li's mother can't take phone calls until after 8 pm and she only sees her children once a year, at Spring Festival. The only dream Li can express freely is, "To go to Beijing and be with mom."

Outside the gate of Li's primary school in Yangfan village, a group of locals leaned on a wall next to a grocery store and kept a watchful eye out for strangers.

Reported cases rise

"Left-behind children with little knowledge are highly vulnerable to sexual abuse," said Ji Hong, who delivers lectures on childhood sexual protection at the China Children and Teenagers' Fund. "It will take a long time to change that."

One of the reasons that sexual violence perpetrated against left-behind children often goes unreported is that the victims seldom inform their guardians about attacks. Most cases that have come to light in cities and rural areas involved children whose parents live at home.

In a report conducted by the All-China Women's federation earlier this year, roughly 47 percent of rural children fell into the 'left-behind' category, and around one-third lived with their grandparents.

In recent years, the number of reported cases has risen twofold, reaching approximately 700 nationwide. A report conducted by Han last year found that most sexually abused children were aged 14 or younger.

According to experts, the paucity of sex education means that rural-dwelling girls of this age have little understanding of sexual behavior, and the advice given by their guardians or teachers rarely helps.

Pilot program

An 18-month pilot program organized by the China Children and Teenagers' Fund in Shanxi will begin in September. Students in the fourth grade or higher (aged 10 or older) from four schools will be taught basic sex education and their parents will assist with the training.

The course will be based on a framework of suggestions for the protection of vulnerable children formulated by the United Nations, but it will be adapted to the local situation, said Xu Xiaoguang, director of the China Children and Teenagers' Fund's international department. "We shouldn't hesitate to educate the entire generation to protect them from harm," said Xu.

The program will also provide counseling for children who have been subjected to violent sexual assault. The basic sex education course will include group study, games and other participation-oriented activities and schools will arrange at least one compulsory class per week. Parents will also be offered the chance to attend lectures.

Children who attend schools that are unable to provide regular teaching sessions will be visited by a mobile group of program members every couple of months. During the course, children and their guardians - either their parents or grandparents - will be given essential education on the children's well-being during their sexual development, said Shen Liping, director of the children's department at the local All-China Women's Federation in Shanxi.

But some parents, like Li Xinru's, need more help from society to help them to protect their offspring from harm.

"Migrant worker parents who live far from their children may not be able to participate in their child's development, but the guardians should keep them informed of events in their children's lives and they should ask more questions themselves," said Shen.

It has also been suggested that migrant parents at companies or factories should attend lectures organized by either their local communities or work unit, she said.

"I know how much parents need to be educated about anything relevant to their child's well-being and development," said Zhang Yingzhang, director of an online parents' group. As the father of girls aged 4 and 7, he feels it necessary to play a part in promoting the program, "Parents really need access to basic sex education."

Li, the introverted girl in the mountain village, phones her mom once a week on average. During the call, she tells her mother everything. "Children can also tell their problems to other, trusted people, not just their parents, as long as those people are caring," said Zhou.

Ji explained that some rural children attend boarding schools, where the incidence of sexual harassment can be high. "They are supposed to be the best solution for the education of left-behind children, but poor oversight and the children's lack of knowledge of their legal rights have had the opposite effect, especially in some recent cases."

Many parents are also reluctant to discuss sexual matters with their children. "Even professionals don't feel comfortable in certain seminars about sex education," said Ji. "So it can be even harder for parents to talk openly with their children about sexual behavior, especially if they don't even live in the same place as their kids."

Children left in their home villages or towns are not the only victims. Those who accompany their parent to live in the cities also suffer problems caused by a lack of proper guardianship. According to the joint survey conducted in Guangdong province, about 75 percent of sexual abuse victims are migrant children living in and around the suburban areas of Shenzhen.

"All these children living on the margins of society will become the next big cause for concern," said Shen. "We should try to deal with the problem in a thoughtful and caring way."

(Source: chinadaily.com.cn)